When I was eleven years old, a friend of mine, Rob, used to live near a large shopping complex called Castlepoint, in my home city of Bournemouth. Like me, Rob was an avid reader, and we would often make trips to the Castlepoint Waterstones (the UK’s equivalent of Barnes & Noble) together. Most of the time we would not even buy books—because buying them new was expensive—but simply browse the rows and rows of shelves. We shared a love of dark fantasy, but like many bookstores, one had to wade through the celebrity biographies and pretentious literary fictionsections to get to the good stuff: fantasy, science-fiction, and horror. These three profane genres, along with graphic novels and manga, were relegated to a secluded place on the first floor, right at the back of the shop, in a curious, windowless nook that took up only six feet by six feet. However, despite the fact our favourite genres had been hidden away, the shop manager possessed the wisdom to make something of this little nook (knowing it would call the most reliable and avaricious of reading addicts), laying out old armchairs, putting up fairy lights around the high, ebony bookshelves, and creating what seemed a little pocket out of time for those who loved fantastical tales, tales of wonder and magic and adventure and horror, tales that stretched the imagination rather than reinforced the bleak zeitgeists of modernity.

My friend and I would often spend hours sitting in that nook, taking books off the shelves and reading them while reclining in the armchairs, discussing our favourite stories, and of course writing our own, though we rarely set anything down on paper. In those days, storytelling was an ephemeral process—and that only made it more magical. I would spend weeks—and I do not exaggerate here, the man hours were absurd—crafting the most compelling narratives my tiny brain could conjure, only to use them all for a one-shot D&D campaign that we would never revisit. But that was their magic, the very fact that—like dreams—they would cease to exist the moment we decided to wake up. Some of my friends still talk about those one-shots; they have become our own personal mythology. They exert more power because we can never get them back, because they have no fixed form. Many writers would do well to remember the pure joy and escapism of this childhood creation. As a recent father, I now recognise that some of my best stories are tales I make up on the spot to help my daughter get to sleep. I wouldn’t dream of writing them down. They are for her, for the moment, and all the more beautiful for how they will fade back into the dreamscape from whence they came after they’re told.

This ritual of visiting Castlepoint’s bookstore with Rob continued for around seven years, until I was eighteen. The only reason we stopped going is because I went to university in another city. Our friendship was not impacted one jot—we’re still friends today, and still read like maniacs and share many books together—but all traditions have their endpoint. But before this end came, Castlepoint Waterstones had one last gift to give me. I am fairly convinced, in fact, it is the last book I ever bought there.

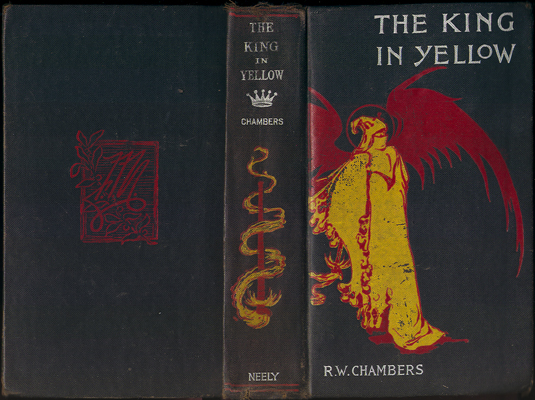

One day, I was browsing the horror section (Rob stood on the other side of the nook, looking at the science-fiction), when I spotted a slender volume. The book did not look like it belonged. What was a Wordsworth Classics edition doing on a horror bookshelf? Surely the book belonged in the classic literature section, which, to be fair, was the only other section of the bookstore I spent much time in (me and Rob were both in agreement that Frankenstein was one of the best novels ever written).Taking this curious book off the shelf, I was surprised by its rather rudimentary cover: a man in a hood with a pale mask—nothing more. The title read, The King In Yellow. I had two immediate thoughts. Firstly, why was the border of the book cover in red not yellow, given its title? Secondly, I thought I recognised the author’s name. In fact, I ignorantly had confused myself, thinking that Robert W. Chambers was Robert E. Howard, the author of Conan. However, mistakenly believing the book might have some relationship with Conan turned out to be serendipitous, given my love of sword and sorcery, and so in a rare moment of spontaneous retail therapy I decided to buy it.

Little did I know, I had just purchased a book that would shape who I am. Not just as a writer, but as a person.

I remember the exact moment I opened the book and realised that something life-changing was about to occur. Unlike my usual procedure, I hadn’t looked at the contents of the book in the store—I normally always perform a “first line test”—something had compelled me to take the book home first. Secure in my room, somehow feeling like I was doing something more profane than simply reading fiction, I opened it, discovering to my great surprise an epigraph in the form of a poem, “Cassilda’s Song”. Opposite the poem was a quote in French, and the opening lines of the first story in the collection, “The Repairer of Reputations”. I was familiar with poetry—in fact, I was an avid devourer of it. And I had read a few books with epigraphs in Latin, modern European languages, or even Japanese. But something about the combination of the two, and the mounting suspicion that this was not a poem written by another author but by Robert W. Chambers himself, that already the book was weaving its magic about me, gave rise to—and I hate to sound like a Lovecraft rip-off here, but it’s the only phrase I can muster that feels true—an indescribable sense of mystery. I knew then, though I’d read but a few lines, that these stories were not going to give me all the answers. They were going to tantalise and tease me like LeMarchand’s puzzlebox, offer me a glimpse of something beyond my current conception of reality.

All of this leads up to me first reading the word “Carcosa”.

What many writers these days do not realise is that words are not just magic in the metaphorical sense, they are magical in the literal sense. Sound is magic; magic is sound. The creation of new sounds is the creation of new meaning. That is why music undoubtedly reigns supreme in the arts; at the very least it is the most universal medium. And that is why one can read a word like “Carcosa” and intuit what it is trying to convey, or rather feel some sense of evocation—like the rising of a memory in connection with a smell, a form of distant synaesthesia—without that word having any contextual framework or etymology that is traceable with intellect. I remember repeating the word several times, ensorcelled by it.

Carcosa was a place described in terms of hushed terror, but awe and wonder too. This is perhaps best expressed by the concluding lines of Chambers’ story “The Court of the Dragon”: “Then I sank into the depths, and I heard the King In Yellow whispering to my soul: ‘It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God!’” More than once reading the collection, every hair on my arm stood on end. The above quote was certainly one of such moment, but there were others. Despite the horror, Carcosa was a place I wanted to go, a place of dreams where one might meet the living God in all His dark splendour. And indeed, it’s a place I’ve revisited many times in my life.

The first time came several years later during 2014 when a show called True Detective aired on HBO. During the second episode, the detective Rust Cohle (played by Matthew McConaughey) reads from the journal of a young prostitute who has been murdered in a ritualistic killing: “I closed my eyes and saw the King in Yellow moving through the forest. The King's children are marked... they became his angels.” As I heard the name of The King In Yellow spill from the lips of Matthew McConaughey’s sociopathically intelligent detective, chills went down my spine. Chills of nostalgia, chills of recognition, chills of anticipation. Cohle subsequently remarks, “It reads like fantasy.” This is a strangely important comment, for it hints towards one of the keys as to why the Carcosa mythos is so enduring and so original. Though it is often described as cosmic horror, and indeed Lovecraft greatly admired Robert W. Chambers and even incorporated the King In Yellow into his own pantheon, The King In Yellow is fantastical as well as horrific, mysterious as well as dreadful, and beautiful as well as strange. Carcosa is not just a black void full of nameless horror, nor is it the horrifying sunken city of R’lyeh (which can only offer us death or madness), it is a place of dark wonders and living fairy tales, a place that you want to reach despite your common sense telling you not to peer too closely into the abyss.

Watching the mythos come alive in the capable hands of Nic Pizzolatto, True Detective’s creator and writer, lit a fire, causing me to dive back into the mythos once again. I discovered to my shock that Robert W. Chambers was not, in one sense, the originator of Carcosa. Indeed, the first mention of Carcosa was to be found in a short story by Ambrose Bierce entitled “An Inhabitant of Carcosa”, a fantastic reading of which can be found here. Bierce’s tale is even more elusive than Chambers’ subsequent interpretation, but what the two share is a sense of loss and a sense of liminality, that however far Carcosa might seem, it is but a step away—and yet, you shall also never reach it in truth. All we can do is stare at the megalithic ruins and wonder. Yet, should we stare long enough, these ruins might begin to speak…

I next visited Carcosa in the hands of Brian Barr. By chance I stumbled upon a short story collection he had released entitled simply Brian Barr's King in Yellow: Stories Set in the Robert W. Chambers' Mythos. The cover instantly grabbed me, not merely because of the phenomenal artwork, but also because it was a similar red to my Wordsworth Classics copy of The King In Yellow, which I still have to this day. I’d never heard of Brian Barr before; he is an independent author, and nowhere near as well known as he should be. But I decided to take a punt. I’ve honestly found more joy and gems in giving independent authors a chance than I have ever found reading big name trade authors. That’s not simply a biased statement from one who is also an indie author (and who’d very much like people to take a chance on him), but the honest truth. Barr is an absolute genius (I’ve read many books by him since), and I found myself riveted from the first line of his astonishing re-imagining of the mythos. Here was somebody not merely homaging Chambers and Bierce but completing re-inventing the theology of The King In Yellow in modern style. He did this partly by incorporating occult elements, such as astrology and kabbalah, into the mythic weave of the story—at the time, I was only just beginning my own study of the occult—as well as introducing alternative history and science-fiction into the mix. I was already inspired to revisit Carcosa, this time on my own terms, but Barr’s modern collection is what really convinced me I had to do this for my own sanity.

It was inevitable—destiny, perhaps—that one day I would try to write a story in the Carcosa mythos. After all, there was a strange synchronicity in that the fateful day I picked up Robert W. Chambers’ work, I was in the presence of another Robert, my friend. That early encounter forever shaped my understanding of dark fantasy, of grandeur and beauty nestled like a pearl in the scum of terror and dread, all the more beautiful for how it is nearly subsumed. For many years, I tried to come up with a tale, but nothing I wrote felt right. I definitely had something to say about Carcosa, but I did not quite know the way to say it. I had wild ideas and concepts, but what was really missing was character. I had the where, but not the who or what.

But then, one seemingly ordinary day in 2022, I was visited by the black goddess Kali, the goddess of bloodshed, ruin, but also creativity, and she showed me the way. She opened the doors of Carcosa to me anew.

It is in keeping with the legacy of Carcosa to leave it at that and say no more on the mysteries divulged to me by this eidolon of my own desires and fantasies, this inner Muse of decimation and beauty. Suffice to say, once she had left her mark upon me, the story flowed and flowed, and I became possessed by it, just like the characters of Chambers’ tales become obsessed and then possessed by the cursed manuscript of the eponymous play: The King In Yellow.

In the words of Chambers, “The time had come, the people should know the son of Hastur, and the whole world would bow to the black stars which hang in the sky over Carcosa.”

That hour is upon us, friends, when the King In Yellow shall return, and all of you shall witness the beauty of Lost Carcosa!

***

You can find out more information about my upcoming book inspired by Carcosa, The Claw of Craving, as well as listening to an extract from the first chapter, here. I’d like to take a moment to thank the incredible folk at Blood Bound Books, Joe Spagnola and S. C. Mendes, for being brave—or perhaps mad—enough to publish my take on the mythos.

There is also going to be a Carcosa-related treat coming soon for those signed up to my mailing list. So, why not subscribe and receive the blessing of the Yellow Sign (you’ll also get a free sci-fi horrornovella right off the bat)?