Our popular culture is plagued by the idea that poetry is elitist and pretentious, and to be fair, it’s easy to see why. Modernism and modern art have tried to change the very basis upon which Art is founded: aka, they have shifted the focus from manifesting the divine within the human sphere towards the realisation of an academic idea or commentary. But where Art is only about ideas, it dies. Enjoyment of Art should not be predicated on contextual knowledge. Yes, all Art exists within a context, that cannot be avoided, but the greatest works resound throughout history and transcend the boundaries of the time period, language, or culture in which they were birthed. I do not need to know what it was like for Dante Allighieri to live as a fourteenth century Italian to appreciate The Divine Comedy. His work speaks for him. This is because real Art must be felt, experienced, and lived. It is transformative.

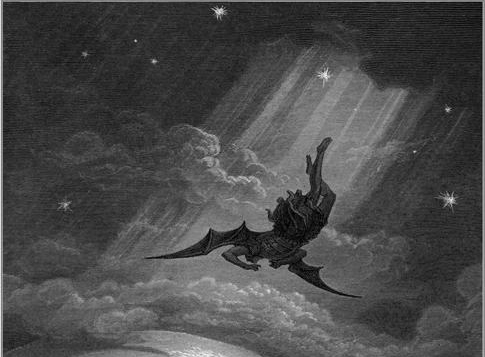

There is a notion that many of the old English writers of the canon, such as Milton, were crusty academics that had no appreciation of what real life was like, yet when we read his work, we find something very different, we find something vital and alive. Milton is, I think, one of the most profoundly misunderstood writers of all time. For a start, his gift for ironic humour is rarely discussed. Paradise Lost is intentionally and spectacularly funny in places, especially when Satan is backtracking over his own warped and impossible trains of thought (Anton Lesser’s magical audiobook reading of the poem particularly highlights this element). But more than humour, Milton’s writing breathes with a tremendous, baroque passion. This passion causes the very form of the poem to bend and even break underneath the weight of his emotion. Indeed, in the very first line, “Of man’s first disobedience…” he disobeys the iambic pentameter of his own line. This could be read as a clever poetic technique, and perhaps it is, but I prefer to see it as a manifestation of the true meaning of the poem coming through. I dare anyone to read the opening to read Book 3 of Paradise Lost—in which Milton begins to realise he is going blind and calls upon God to help him finish the poem—and not be shaken: “but thou / Revisit’st not these eyes, that roll in vain / To find thy piercing ray, and find no dawn;”

This is where poetry differs from prose, and why we still need poetry in a world flooded with memes and literalism. I should say, before I go on, that I am not one of those elitist poets who believes in the superiority of poetry. How could I be? I am a novelist too, and I love novels! However, after years of rejecting and suppressing my inner poet, and then facing and unleashing this inner passion, I am forced to conclude that poetry offers something prose does not and never can, which is a way to stir the deepest tides of the human consciousness with merely a few lines. There are many reasons that the resultant outpouring of feeling can be so powerful. Rhythm is one. In other words, great poetry can affect the mind in the same way as music using alliteration, meter, and other formal techniques. This way, poetry can imbed the meaning of the words far deeper than prose. Don’t get me wrong, prose has rhythm too, but poetry cuts deeper.

The second way is via rhyme. Rhyme is commonly misunderstood. For many modern commentators, rhyme is a pointless exercise, the poet simply “challenging” themselves, but this is a masturbatory view. The real purpose of rhyme is to link two ideas that would not normally be linked. When words rhyme, we begin to infer an association, however off-the-wall. For example, if we rhyme love and dove, we link the concept of human “love” with “peace” as the dove is a symbol of peace. Those two words have been rhymed far, far too often, so it is no longer an interesting rhyme to use, but you get the idea! We can also use para-rhyme (which includes vowel-rhyme and consonantal rhyme). For example, rhyming love and live is a consonantal half-rhyme. Rhyming wound and noon is a vowel-rhyme. This gives us access to a huge, huge range of possibilities, and given the English language has the fastest growing vocabulary in the world, and the most words, we are unlikely to exhaust the possibilities any time soon!

Of course, bad poetry uses predictable or monotonous rhythm, and cliched and unoriginal rhyme, which destroys the potency of the verse. But the existence of bad formal poetry does not mean we should throw all formal poetry out, just as my inability to kick a football straight does not mean we should ban football as a sport.

Poetry is a large and daunting field, despite the fact that people are eternally claiming “no one reads poetry” anymore. The truth is: people do, as the many YouTube channels dedicated to the study of poetry attest. The world is hungry for it, but some people may not know exactly what it is they are hungry for, because the field is so rife with politics and loaded with historicity.

Not only this, but great poets introduce new phrases into common speech all the time. We are forever loaning the words of poets, even if we don’t know the names of those poets. Percy Shelly said that poets were “the unacknowledged legislators of the world”. Whilst the statement is lofty, when it comes to language, it’s hard to deny its truth. And this brings us to one of my favourite quotes from Alan Moore: “Words offer the means to meaning, and for those who will listen, the enunciation of truth.” This, perhaps, might be the very definition of poetry itself! The thing about truth is it’s like the sun. We can’t look at it head on, because it would burn our eyes out. However, poetry, unlike prose or any other medium, can reveal the truth more obliquely. The seeming “weirdness” and veils of poetry allow us to glimpse the truth without being blinded. There is a powerful link between poetry and magic which is too deep to go into here.

So, where to begin? No two poets are the same, though some have much in common, and ultimately we have to find the poet or poets who speaks to us. Arguably my favourite poem of all time is Childe Roland To The Dark Tower Came, by Robert Browning, which is one of the greatest pieces of literature ever written in my eyes. You can watch me doing a reading of it here. It is not too long and the language and feeling is awe-inspiring. Its meaning cannot be easily précised, but think about what the hero confronts at the end: is it death? despair? self-annihilation? guilt? Then consider how the hero faces it. Hair-raising stuff!

I also personally adore the work of Edmund Spenser, but many find him a little too formally rigid for modern tastes, and the size of his poems makes him difficult to get into. I find he is worth the effort though! My own upcoming work, Virtue’s End, is heavily inspired by Spenser’s Faerie Queene.

If you are looking for contemporary writers, though I am completely biased, I would have to recommend my wonderful father’s epic poem, HellWard, as a starting point. The poem deals with his battle for cancer in the ward of a hospital which, as the title would suggest, is not all that it seems. Though epic poems can be daunting, the great thing is that they have narrative propulsion, which makes them a good starting point for someone who is new to poetry, or just looking to test the waters. We can follow the narrative and if some of the imagery or references go over our head, that’s okay, because we’re on a journey. After a while, we sink into the rhythm of things and realise our bearings. Another incredible modern epic poem is Andrew Benson Brown’s Legends of Liberty, which is a historical mock-epic set during the American war for independence. I previously reviewed this dazzling, hilarious, and moving work here.

Poetry is not for everyone. Except, I actually think it could be. That’s because real poetry isn’t understood with our left-brain, that is clouded by biases and intellect and judgement, it’s absorbed somewhere deeper, in the very soul, perhaps—though we have to open ourselves up to it. Any time we respond to a painting, piece of music, or literature with that unfettered, even explosive, emotional reaction, we are getting to the heart of what great Art—and poetry—is about. Archibald MacLeish once wrote, “A poem should not mean, but be.” In a world of ever more divisive opinions and politics, real poetry asks us not to decipher or argue, but to enter that immediate, present, and timeless being and feeling state. In the words of Emily Dickinson, “Forever is composed of nows.”

Become a Patron!