Hello, and welcome to what will be the final instalment in Entering Carcosa. It has been a fabulous and rewarding experience writing about these epics, and I hope that anyone reading these has found inspiration for their own work. I am going to post links to the six previous articles here for ease of navigation.

Part 1: The Epic Isn’t Dead

Part 2: Metal Gear Solid

Part 3: The Horus Heresy

Part 4: True Detective

Part 5: The Book of the New Sun

Part 6: Seven Deadly Sins

For this last episode, I intend to write about an epic novel. Yes, I said I wouldn’t do it, but this novel is an exception because it is such an anomaly. Not only has the novel been largely forgotten, but the author too remains fringe even though they continue to write intriguing books today. It is a novel of incredible paradox and contradiction: as poetic as it is pornographic, as profound as it is problematic. The novel in question is Eric Van Lustbader’s Black Heart. It’s no secret that I am a huge fan of Lustbader, but what I find startling is how little credit he is given for his lyrical style. Whilst he is most famous, perhaps, to modern audiences, for continuing the late Robert Ludlum’s Bourne series, I find his personal projects far more remarkable, not simply for the stories he tells, but the way he tells them. Why is this epic poet neglected, then? I think, there are a number of reasons.

Firstly, let me tell you how I came to read this novel, because the process itself was something on an epic journey. This is a long book: some 800 pages, and easily over 240,000 words. I had picked up a battered old copy from a local second-hand bookshop around two years ago. I enjoyed Lustbader’s first book The Ninja greatly and wanted to read a standalone by him. I got to roughly 50% the way through the novel, when my duties as a fiction reviewer got in the way. I told myself I would finish up reading some of the new books I had to review, and then return to Black Heart. The problem was, the book was so complex, with so many characters and intersecting plot-lines, I couldn’t get back into it. I eventually had to abandon the attempt. For two years, this book kind of haunted my imagination. I rarely give up on books, and especially not books I was enjoying. Odd scenes that I could remember from it went round and round in my head.

Eventually, I realised I had to finish it, so I decided to once again attempt it. This time, I was able to easily blast through it. The feeling of deja vu and synchronicity reading it for the (sort of) second time only added to the mythical weight of the some of the scenes. This was made even more weird by the fact that the 1984 re-print that I had a copy of was littered with copy-editing mistakes. I mean, tonnes of mistakes. And not small ones, but full word-replacements and repeated lines and missing sentences. Reading it became a kind of scholastic activity rather than merely a leisurely one, like filling in the blank spaces left in Anglo Saxon poetry manuscripts. How could there be so much here but also there be so much missing? I became obsessed and fascinated to the point where I considered reaching out to Lustbader to work with him producing a cleanly edited version of the novel. I felt angered he had been so deeply let down by the publisher, I would hate to suffer such negligence myself.

Why am I telling you all this? Well, because I think it tells us something interesting about Black Heart. For many reasons – it’s action, sex, intensely passionate writing style – this book is considered pulp. Yet, how easily do we forget that the great Homeric epics are practically bursting with vicious combat scenes, sensuous affairs and sexual encounters, and written in a style that defies traditional writing conventions. In other words, I think it shows we have confined what was once epic to the pulp shelf, and now praise – well, whatever stuffiness stepped into its place.

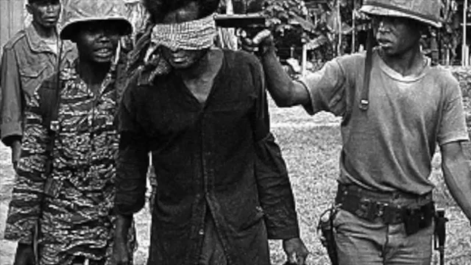

Written in 1983 and subsequently republished, Black Heart is about the Cambodian genocide of the 1960s and a group of inter-connected special-operatives at once haunted by the past and struggling against sinister forces behind the scenes in the present. It is a strangely prescient book, predicting a rigged American election with Russian influence and corporate backing. The presidential candidate depicted in Black Heart, Atherton Gottschalk, is even a kind of Trump parallel, with an obsession with protecting the borders of American from ‘foreign invasion’ and deploying the military to safeguard American ideals. Gottschalk’s paranoia about terrorism, with frequent monologues about the nature of Islamic terrorist attacks, becomes frighteningly foreshadowing, in some ways predicting the fall of the Twin Towers in 2001, an event which would occur eighteen years after the book was published.

Gottschalk is being put into power via the machinations of several parties. At their heart is Delmar Davis Macomber, an elite American operative stationed in Cambodia who now runs a weapons manufacturing corporation called Metronics Incorporated. However, this company is but a front for a secretive organisation founded in the blood and atrocity of Cambodia, one that is prepared to kill to exert its influence over Western politics. Whilst Macomber may seem a villain, and even sports a villain’s moustache, Lustbader is never so simplistic, and offers compelling motivations for Macomber’s behaviour. At one point, roughly halfway through the book, our impression of Macomber shifts dramatically as new information comes to light and he transforms almost into the truly wronged party and one of the heroic figures of the narrative.

The true protagonist of this novel, however, is Khieu Sok. Khieu is an assassin in Macomber’s employ who began life as the son of a wealthy Cambodian family and a devout Buddhist. During the communist genocide, he joined the Khmer Rouge and turned on his own family and ideals in order to survive, committing atrocities to maintain his life. He was taught the art of stealth and hand-to-hand combat by the Khmer’s ‘secret weapon’, a Japanese martial arts master called Murano Musashi (a nod to the real Miyamoto Musashi, widely regarded as the most legendary swordsman in history). Macomber ‘rescued’ Khieu from his violent life in the communist regime only to manipulate him into carrying out high-profile assassinations on American soil. If you are thinking that this sounds vaguely like the plot of a Tarantino movie, you would not be far wrong. Lustbader’s love of unarmed combat is unabashed and he sees no problem delivering some of the most memorable and ultra-violent fight sequences in fiction. However, to say Black Heart is all action would be a gross miss-sell; it is just as concerned with introspection as it is with high-octane adrenaline, just as intrigued by the sundries of life and what deeper meaning they may hold, as it is with vividly described anal-play. It is full of life and willingly embraces all facets of life, whether they are palatable or not.

Khieu is the heart of this novel all about heart. He is dichotomy personified, at once viewing himself as a Buddhist and therefore pacifist and holy, and also as a weapon of mass destruction and cold-blooded killer. Khieu has compartmentalised his life, and slowly throughout the course of the book the strain of holding these contradictory identities in mind tears him apart. The counterpart to Khieu is the seemingly ‘heroic’ Tracy Richter, another American who fought in Cambodia as part of a secret operation connected with Macomber. Tracy appears to be the classic ‘good guy’, a match for Khieu, having also been trained by a Japanese martial arts master Jinsoku-san. However, we slowly realise throughout the book, as we learn more about Tracy’s past, that in fact he enjoys killing. Like Khieu, he is victim of double think. He sees himself as a loving partner to his true love, the ballet dancer Lauren. A loyal son to his father, Louise Richter, who also plays a key role in the novel. But he also loves the power of ending a life. It’s a dark and morally grey portrayal that catches us off guard. Who do we really root for? The warrior who is trying to be a Buddhist, or the warrior who embraces what they are?

Just as Khieu and Tracy embody the juxtaposition of conflicting identities, Black Heart is similarly a book of incredible dichotomy. Double-think is present throughout the entirety of the novel. On the one hand, the most intelligent character in the novel is probably Kathleen Christian, a woman whom we initially believe is being used by Atherton as a ‘bit on the side’ but slowly realise is actually the one manipulating the presidential candidate. Her intelligence and cunning are an intriguing and complex counterpoint to the more directive schemes of men like Macomber. However, on the other hand, she is sexualised at every possible turn, as are all the female characters. That is, until they are murdered. Black Heart revels in its violence and explicit sex; you can tell by the language and the verbosity with which it is described. Yet, it is also about transcending both of those things, which is Khieu’s ultimate character arc. It simultaneously exhibits both positions without shame or fear.

Lustbader does not fall into the Madonna-Whore trap that so many male writers do. He manages to portray women who have complex sexual identities but also moral dimensions and intelligence. Lauren, Tracy’s partner, proves to be a key player at the end of the novel, and it is her act of astonishing courage at the novel’s denouement that saves Tracy’s life and redeems him. At the same time, Lustbader never misses an opportunity to tell us just how great her breasts are. Given how explicit and graphic some of the sex scenes in this book are (sex that makes D. H. Lawrence and Byron look like rank amateurs) one can kind of see why he zeroes in on these physical endowments. He sexualises the men, too, after all. Does this make it okay? Perhaps not, but it shows that Black Heart has its own kind of weird internal logic and consistency, and it is these through lines that I believe make it great and worthy of the epic. Khieu, as a subversion of the epic hero, has a unique weapon, which is his magnetism. His martial ability is secondary to his ability to lure people, men and women alike in fact, to him. Like a Gorgon, he often transfixes them with his eyes before striking the killing blow.

Thematically, Black Heart is mind-meltingly rich. The direct derivation of the title is an alternative name for the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, who refer to themselves as a Chet Khmau. It also becomes a kind of pseudonym for one of Khieu’s bifurcated personalities as his violent side emerges more strongly. In Western language, the word ‘heart’ is directly derived from ‘courage’. Corazón in Spanish means both. Le cœur in French is similarly synonymous. In Japanese, kokoro literally means heart or ‘inner mind’. However, we are given two deeper definitions of kokoro by the two different Japanese masters in the novel. Murano Musashi, Khieu’s master, defines it: ‘The killing spirit is here. Believe that if you believe nothing else.’ This echoes Stephen King’s world-famous line from The Dark Tower: ‘I kill with my heart’.

The second definition we receive, however, is even more profound. Jinsoku, Tracy’s master, tells us that ‘To peer into this and survive is life’s only heroic act’. To look inwardly, to truly interrogate ourselves, in other words, is the only heroism. Interestingly, I think Black Heart itself asks for our heroism as readers, for us to look beneath the surface and work out what the real mystery is, and this book is full of mysteries right up until its final page. The deeper into the past it plunges, the more we hunger to learn and the more we realise we can never know. Tracy says ‘the past holds the key to everything’ (this becomes a segue-way for the first flashback in the book), and in the case of this story he is utterly right. All of the characters are connected by their traumatic past and are drawn back to it. As F. Scott Fitzgerald once said: ‘So we beat on, boats against the current, drawn ceaselessly back to the past.’

Each character in the novel, regardless of how major they are, is required to look inward, to ‘peer into kokoro’. Tracy refuses at first to look inward, unable to acknowledge the ‘vice of killing’. Lauren cannot admit how she really feels about Tracy. Her heart is literally in the wrong place. Khieu cannot order his binary identities. Macomber cannot interrogate his motivations and therefore transcend them and let them go. There is a kind of ironic touch in that one of the weapons Macomber’s company, Metronics Inc., is working on, is called the Vampire, a new type of AI-controlled fighter jet. Vampires, of course, can only be killed by putting a stake through the heart.

Atherton Gottschalk’s ‘black heart’ is semi-literal, a weak heart he is terrified will give out on him due to genetic defects running through his family. When Macomber stages an assassination attempt on his life to boost his popularity, he is shot in the heart. Even though he was wearing a bullet-proof vest, the experience unmans him. In the end, once Macomber’s plot and his artificially boosted bid to presidency is exposed, Atherton kills himself because he lacks the courage to face the press and shame.

Black Heart, of course, also evokes the Chinese philosophy of ‘Thick Face, Black Heart’, first postulated by Li Zongwu and later developed by Chin-Ning Chu. It is a sociological technique of concealing one’s true motivations in order not to be victimised by the world. This philosophy is so nuanced that to restate or summarise here would be to grossly bastardize and do it injustice. However, conceptually it marries with a lot of what Lustbader thematically explores in Black Heart. No one is who they seem. People who seem altruistic prove selfish, and people who seem selfish prove devotionally selfless.

One of the most fascinating characters in this regard is Kim, a Vietnamese master-torturer. It would be easy to hate Kim, especially in the hands of another writer, but Lustbader shows remarkable empathy in his portrayal of a (literally) tortured person. Kim has watched the genocide of his people and the decimation of his entire culture. His story, which proves more relevant to the main plot than we could ever imagine at first, is in some ways a ‘last human on Earth’ narrative – a man out of time and place who has nothing in common with the rest of humanity, who feels utterly alienated by Europe and America, where he is forced to survive. Kim is consumed by the flames of the past and a desire for revenge. Yet, his motives are not selfish as they first appear. He acts on behalf of his family, all of whom save his brother were killed by Cambodians. Kim’s interactions with his brother are some of the most fascinating in the novel. His brother, Thu, has embraced Western culture, marrying a blonde American woman who seems the epitome of American beauty and 50s domesticity. Kim, however, cannot let go of the past and who he is. It is about how the West has trampled on cultures and subsumed them.

Throughout, Lustbader invests massive time and energy making his characters, particularly his Asian cast, feel real and three-dimensional. I couldn’t stop myself asking how many major books, films, and games of the last ten years have over 50% of the main cast made up by Asians, and not only that, but a diverse range that pays subtle attention to the colossal cultural differences between Japanese and Chinese ways of life, Vietnamese and Cambodian, and more. Is Lustbader culturally appropriating, or is his work a Shakespearean achievement of sympathy and recognition in the vein of The Merchant of Venice? It is not for me to say, of course. Others more qualified will be the judge. I can see that if this novel were to be released tomorrow, it would be extremely divisive in this regard.

In fact, I’m not sure this kind of novel could get a major publishing deal nowadays, not because I do not think it is up to standard, but because it is too radically what it is. It is lavishly stylistic, borderline psycho-tropically sensual, and doggedly true to itself. No overzealous editor has paired down Lustbader’s ferocious prose, and that is entirely a good thing. There are so many vast droves of sterile, boring books these days that have been edited into oblivion and unmeaning. Black Heart is not one of them. It does what its blurb says: ‘Explodes with supernova intensity’. Is it a little much at times? Maybe for some readers, but I personally found myself riveted from word go.

Lustbader isn’t afraid of an extended metaphor, nor a mixed one for that matter. Just look at how he describes Khieu feeling once again the loss of his sister, for whom he had an incestuous infatuation: ‘His right hand would ache and he’d look around wildly, feeling the heated breath of the unknown furnace closing on him, brushing past him just a heartbeat away.’ That final line is transcendental, not only connecting to the title of the book but also transporting us with an auditory stimuli rather than a visual. Sound, of course, has far more of a capacity to transport in time than any other medium. Just think of hearing an old song and the way it puts you into that exact location in time. Similarly the ‘heated breath’ of the furnace is psycho-sexual, as is the use of the word ‘brushing’.

Not all of Lustbader’s sex is perverse either. Sometimes, he surprises you with something wholesome, or else deflates or interrupts the sexual congress with some startling revelation or observation. Let’s examine again Khieu’s obsession with Malis, which is in part an act of semi-religious devotion in which he describes her as ‘apsara’, an interpreter of the gods. In one traumatic flashback, a young Khieu watches his sister Malis masturbate in bed, a voyeurism he succumbs to nightly, only to then have his fantasy destroyed as Malis’ real lover climbs through the window in the dead of night. It’s a shocking moment, for us and Khieu. Khieu becomes aware of himself as an observer, and sees the baseness of what he is doing. It is a startling moment where we as readers are also jerked out of the passionate frenzy and come to see ourselves as slightly perverse voyeurs.

In Black Heart, the ultimate katabasis, the ultimate hell, is the past itself. Just as we drawn back to it, so too we are haunted by it. All of the heroes are literally drawn back to China and Cambodia, and their respective pasts, where they discover numerous horrifying revelations. However, in the final sequence, we return to the past in a spiritual and symbolic sense as Khieu finally sheds his guilt and once more returns to the beauty of Buddha which he glimpsed as a child. It is a hair-raising scene that caused me to profusely weep, a moment of divine revelation in which the entire meaning of the cosmos hinges on one profound image: ‘… at last he saw the eternal face of his Amidha Buddha…’ Black Heart, for all its love of action, ends on a note of spiritual re-awakening.

All of the characters are called to free themselves from the past and let go of old grudges, to purify their black hearts. Tracy Richter is utterly defeated; he does not triumph over the villain in physical combat. However, he learns that there are more important things that settling the score. Khieu, similarly, stops fighting and becomes one with the Buddha whom he adored as a child. Kim, however, is another story, eaten up by the flames and cast down into oblivion, all because he cannot let go of the wrong done to him. Black Heart is strangely a tale of redemption that offers the surprising revelation that it really is never too late, provided we do not allow ourselves to be conquered by our desires and temptations. It has been said that the Western story is characterised by the straight line, the journey, and the Eastern story is characterised by the returning circle. Whether this is true or not, Lustbader reflects this tradition by having his novel circle fully back to the profound opening line: ‘From within the eye of the Buddha, all things could be seen.’

Black Heart is honestly unlike anything I have read in the world of fiction or am likely to read again. It changed the way I think about narrative and prose in startling ways, and offered me a glimpse into an astonishing time period and historical event that in the West we still know very little about. I could not help but feel a profound sadness as I put down the book. It was the sense that something truly great, for all its flaws, had been lost from the world, was no longer remembered as it should be. But then, that is very fitting, as the very message of Black Heart is to let go of the past.

X

This has been the final entry in the Entering Carcosa series. I hoped you have enjoyed investigating these modern epics with me. The only thing that remains is for you to write your own.

I will not be disappearing, however, far from it. I’m looking to transition these discussions about literature, films, movies, games, and more, to another medium, possibly a podcast, though I haven’t fully made my mind up yet! Keep your eye out, especially on my Twitter: @josephwordsmith. If you ever need help, advice, or simply someone to rage against the world with, feel free to message me there! Also, if you have any suggestions about the kind of content you would like me to produce, people get in touch via this website’s contact page or Twitter.

If you feel that you have benefited from today’s class, then please check out my KoFi page, where you can donate $3 to “buy me a coffee” to help me keep producing free resources like this. Do not feel pressure to do so, but small contributions can go a long way for creators like me.

Thank you, my friends!